The Civic Necessity of the Public Editor

Everyone claims to want accountability. This thing happened; that person is responsible; and if it's you who is responsible, you have to accept the consequences. It's a truth drilled into us as kids, and it's a central underpinning of the rule of law.

But look around. So much of our societal, cultural, and literal infrastructure feels corroded and unattended. Who is responsible when a skyscraper-sized container ship destroys a bridge? Who’s to blame when we’re optimized out of a job? Who’s fault is it when a mentally ill person, abandoned by society, commits a horrendous crime? And down the line, through our enshittified digital experiences to what we see, hear, and read.

Things are broken, but no one’s at fault. Mistakes were made; no one’s to blame.

Journalism is societal-lack-of-accountability in microcosm. It's the Fourth Estate, a necessary check on power that would otherwise not check itself. It afflicts the comfortable and comforts the afflicted. But where is the check on journalists? Who keeps them honest and ensures they don't get too comfy?

These days, no one. And the consequences have been disastrous — for readers, for publications, for democracy.

I've been thinking about this a lot since now-former NPR editor Uri Berliner dropped his self-pitying NPR-has-a-liberal-bias temper tantrum on Bari Weiss' self-pitying temper-tantrum platform Free Press. Specifically: For someone who worked at NPR for as long as Berliner had, he sure seemed to be out of step with who NPR's audience is, what they expect, and how that informs what NPR is. And we could sure use a public editor right now.

As it happens, NPR does have one: Kelly McBride, an external consultant who's real job is senior vice president at Poynter and chair of Craig Newmark Center for Ethics & Leadership at the Poynter Institute. McBride did weigh in, sort of from the side, on the Berliner essay twice, first in a column and then in a newsletter. But the stories that got the most play online were by NPR's media correspondent David Folkenflik.

There's something telling in a media reporter's stories getting shared more than NPR's public editor. I suspect it has something to do with a cultural fetishization of media coverage. (Seriously, we have too many media reporters. For no good reason.) I think it also reflects that readers, audiences, anyone who cares about the health of media and journalism want reporting about why their favorite publication did this or that or has been accused of being something or other. Commentary and reader mail bags only go so far.

And that's where a robust, empowered public editor can do a lot of good.

It wasn't that long ago that some of the biggest publications in the nation had public editors on their staffs. The Washington Post had an ombudsman for decades. The New York Times created the role in 2003 in the wake of the Jayson Blair scandal. Then the Post and Times eliminated the role in the previous decade. And for very similar reasons: money — the job cost too much — and technology. "It is not as if The Post doesn’t come in for criticism, from all quarters, instantly, in this Internet age," then-Post executive editor Marty Baron said when cutting the position in 2013. Four years later, then-Times publisher Arthur Sulzberger went further, saying "our followers on social media and our readers across the internet have come together to collectively serve as a modern watchdog, more vigilant and forceful than one person could ever be."

Let's pick on the Times because it's the Times. 1) Have you seen the internet? It's not what anyone would confuse with actual accountability. And 2) his explanation was a kiss-off dripping with hubris.

The Times had six public editors in the position's 14-year existence: Daniel Okrent, Barney Calame, Clark Hoyt, Margaret Sullivan, and Liz Spayd. We can argue about the state of the paper in those years and the success of those public editors. And surely a lot has changed since. For starters, the Times has evolved into a tech company. But can anyone honestly say the Times — and its readers and subscribers — would not have benefitted from a public editor taking the reporting lead on the James Bennet–Tom Cotton imbroglio? Or from getting to the bottom of its wretched both-siderism and headlines? Or from helping make sense of all the generational and ideological in-fighting? Or from looking at the Caliphate scandal? (And that's just for starters, off the top of my head. It is seriously exhausting trying to support the Times.)

All of those controversies fed their fair share of online outrage cycles. But online outrage is not the same as accountability. And even if the Times believed — believes — it's above and beyond reproach, its readers deserve better than a publication claiming to be too big to critique. The public editor is an internal watchdog, but more importantly, when they're good at their job, they are readers' representative. "The responsibility of the public editor ― to serve as the reader’s representative ― has outgrown that one office," Sulzberger said in 2017. Maybe. But the answer would be to hire a second public editor, not diffuse the responsibility to literally everyone in the world.

Argue all you want about the utility of the job, it's undeniable that a public editor is a person with a face and name and email address and phone number and social handles that readers can go to when they need... whatever it is they need. The public editor holds a publication accountable but is themselves held accountable by readers. This is how journalism used to work: reporters, critics, editors knew they were in a community, and that alone was a check on their worst impulses. It's harder to do shoddy investigations or flame someone or write crap headlines if you know you'll be taken to task by your neighbors when buying groceries.

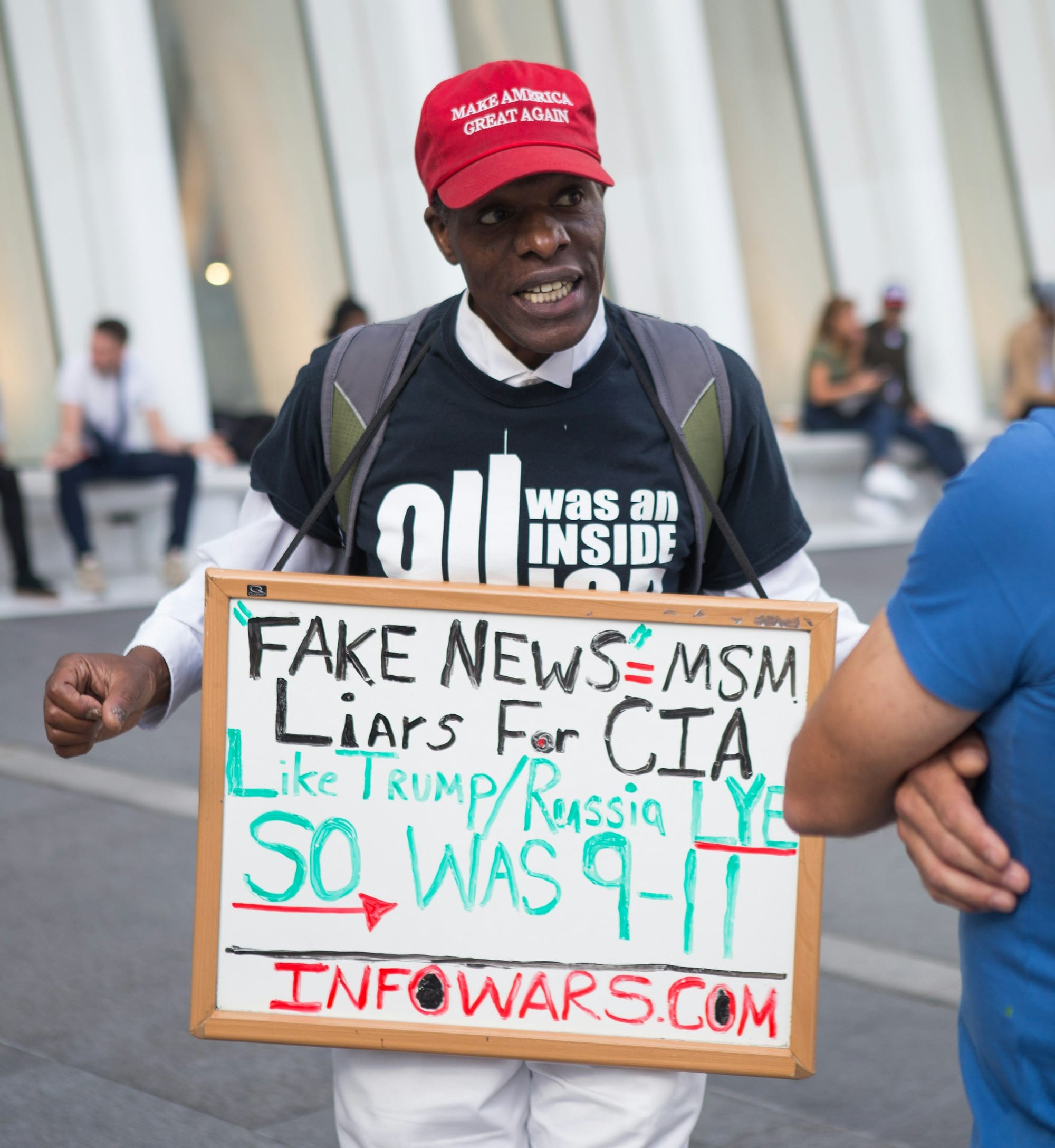

In absence of human accountability, where does one go to vent, ask questions, demand a retraction, get heard? The comments? Twitter? A vanity newsletter? They're fig leaves publications can point to as evidence that they care. But they're also easily dismissed as noise, bad-faith, haters. That, I think, is a core factor in why so many Americans hate the media so much. The elitism is real. The echo chamber is real. The lack of diversity — racial and class — is real. But unlike in decades past, there's nowhere to turn for a reader seeking answers, clarifications, or simply an ear to bend.

Anyone who has ever worked in a service industry job knows that simply acknowledging a complaint is enough for most people. The problem festers and metastasizes when you ignore it or treat it as beneath you. Then the human with the issue is stripped of their voice, their agency, their dignity by a body that's bigger, better, more important. And for many Americans, this is the dynamic they face with media. In many ways, journalism has taken on the qualities of its Silicon Valley host body. In shackling its business to platforms' black box algorithms, the industry itself became a kind of black box, mysterious and impenetrable, convinced of its own inevitability, and totally above reproach.

Journalism is a noble, necessary profession. But it is not inevitable; there's a reason the First Amendment exists. Nor is it an Olympian occupation of mystery that only the chosen can touch. It's a service job. We who practice journalism serve our audiences, our communities, our national interest. (A conversational road to be taken another day: the emergence of the term "citizen journalist" reveals the elitism and exceptionalism that has swallowed the industry.)

The public editor is, in its way and when practiced well, the embodiment of that spirit of service. It's the bridge between publisher and audience. And it's a good-faith show of accountability — something in desperately short supply. The resuscitated public editor won't close the credibility gap overnight, but it could allow us to have the hard conversations about what ails American journalism and begin to pull out of the tailspin. We should demand its return.

Recommended reading for public editor true-believers: Public Editor #1 : The Collected Columns (with Reflections, Reconsiderations, and Even a Few Retractions) of the First Ombudsman of The New York Times by Daniel Okrent; and Ghosting the News: Local Journalism and the Crisis of American Democracy by Margaret Sullivan. (Also Sullivan's Guardian newsletter is worth a sign-up.)

Comments ()