Netflix is Becoming an Old Hollywood Studio — It Should Act Like One and Buy Some Theaters

Netflix can make vertical integration (and maybe movie theaters) great again!

This morning, Netflix announced it was acquiring Warner Bros. Discovery for $82.7 billion. The deal gives the streamer everything but the cable division, which will be spun off. It also, unofficially, feels like it turns the clock back to the 1940s.

The anti-Blockbuster, anti-theater tech company who set fire to Hollywood and salted the earth in its wake; whose leaders once said were in competition with sleep — has made a play for one of the all-time legends of Tinseltown. And with the acquisition bid, Netflix claims it will be in the business of releasing movies theatrically.

What’s a streamer when it’s no longer streaming-first?

Let’s be clear: This is hardly a done deal. To say mergers like this have gotten political in the last year is a massive understatement. And this is 2025's merger of mergers. Will the FTC block it? And if so, will it because of some quid pro quo? Will we ever see the red Netflix N on the iconic WB water tower? Who knows.

But let's also be clear: Netflix buying Warner Bros. is bad. It’s bad for viewers — less choice. It’s bad for artists — less freedom. It’s bad for Hollywood — fewer players. It’s bad for culture — increased homogenization. And it’s bad for America. Netflix owning, at the least, HBO Max is so clearly a monopoly I half expect to see a TikTok of Theodore Roosevelt’s corpse smashing up Ted Sarandos’ office.

(Does it matter that the alternative — David Ellison’s political hot potato Paramount gobbling up WB — is far worse? Maybe. And it’s also possible that Ellison, who threw an entitled-rich-kid hissy fit ahead of the Netflix announcement complaining that the bid process was “unfair,” will grease some palms in Washington to ensure the FTC nixes the deal, clearing the field for a renewed bid.)

But we have to look at this in the context of the world we live in, not the one we fantasize. America has been OK with monopoly power for decades, its ease only growing as with each successive presidential administration. (Lina Khan heading the FTC under Biden being the exception.) So if we start from that point — America believes monopolies are OK — how does the Netflix/WB deal look?

Still bad. But in the spirit of our up-is-down times, if you squint the right way there’s a scenario that’s not so far-fetched that could lead to something positive — if only for viewers.

Before we get to that, we need a brief history lesson.

The movies in America were born and raised in monopoly and oligopoly. In the early 1900s, The Motion Picture Patents Company, created by Thomas Edison and a hive of film producers, controlled patents and distribution and levied staggering licensing fees on its movies. It also sued, or threatened to sue, into oblivion any upstart independent that tried to make their own movies. Hollywood forefathers Carl Laemmle and Adolph Zukor decamped New York for California to escape the trust’s iron grip. The Supreme Court finished the job in 1915, when it ruled the trust an illegal restraint to trade.

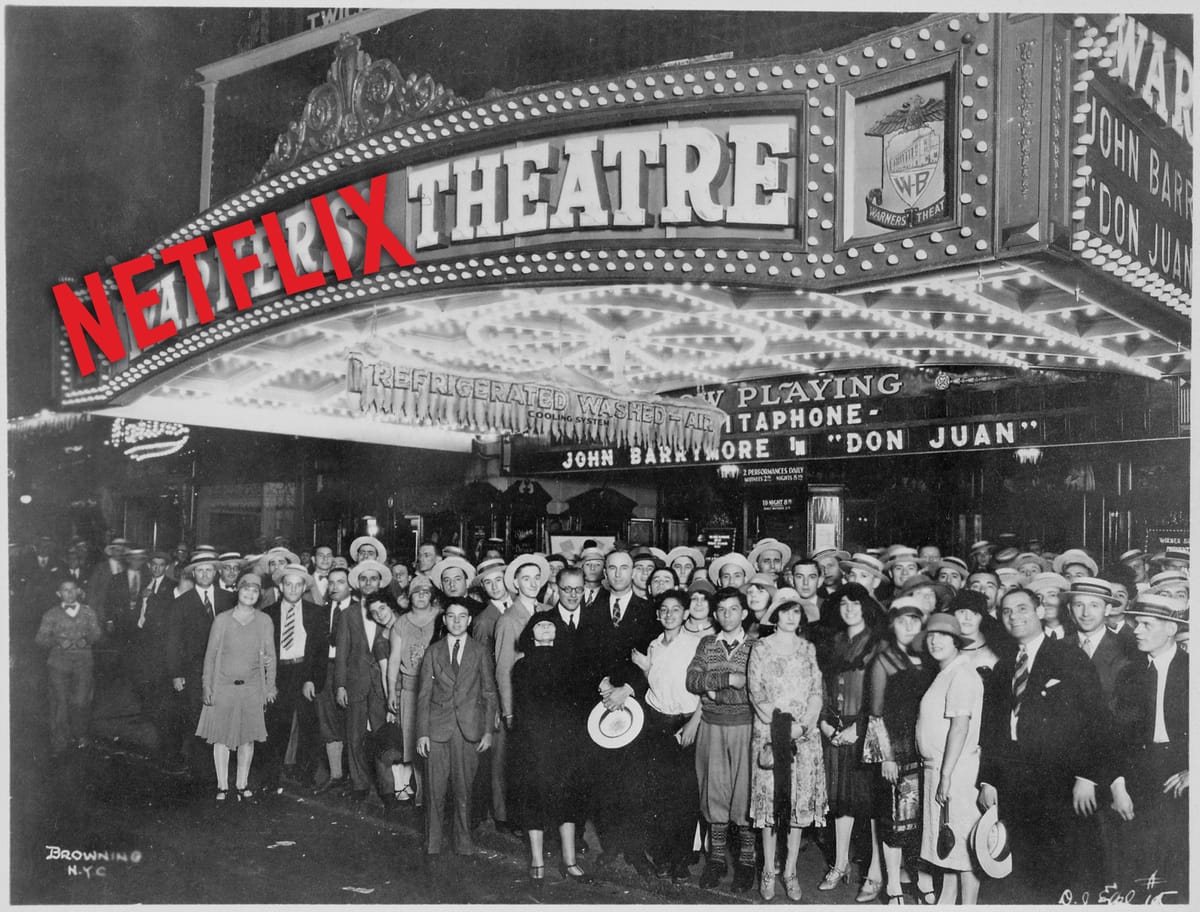

That decision allowed Hollywood to blossom and become the world’s dominant film factory. And it worked on a system of vertical integration. Studios held contracts on talent, made films on their lots, and released them into theaters they owned, often through a system of block booking. If a theater wanted the latest Bogey and Bacall feature, they also had to take a slate of B-grade junk the studio had pumped out. But like the Motion Picture Patents Company, the Supreme Court eventually came for La La Land and in 1948, in US v. Paramount Pictures, Inc., deemed the studio system violated antitrust laws. Like in 1915, the Paramount Decree opened new possibilities for filmmakers, producers, and theater owners to get a piece of the movie business.

Paramount was the law of the land until a Department of Justice review in 2018 led to a termination of the decree in 2020. Now, studios could once again make movies and own movie theaters. And wouldn’t you know it? Netflix, of all companies, bit, buying in late 2019 New York’s one-screen Paris Theater — which originally opened four months after Paramount was decided — as a venue to screen (ostensibly for awards consideration) movies it made that would otherwise originate via its streaming service.

Which brings us to now. Assuming the deal goes through, Netflix will own Warner Bros by the third quarter of 2026. It will find itself with a legacy studio with an incredible library, a stacked IP lineup (including Superman and Batman and the rest of the DC Comics universe), and a brand that people — viewers and creatives alike — love and equate with in-theater experiences. And it will find itself on the hook, having promised to keep releasing WB movies in theaters. And that will put it — once again — into conflict with the National Association of Theatre Owners, which historically has enforced a hard line against Netflix movies. If it doesn’t follow the trade group’s rules for theatrical-release windows, its movies will not be booked in NATO theaters. (This, famously, happened with Martin Scorsese’s Netflix-produced The Irishman — a film Paramount refused to fund. A ridiculous self-own on NATO’s part in a bid to claim victim status in the war against streaming.)

So if Netflix makes movies it can’t release theatrically, what will it do? Here’s a suggestion: Netflix should vertically integrate. And it should do it by acquiring the AMC theater chain.

Audiences have fled from theaters not only because of the ease of streaming, but because, by and large, going to the movies is a massive pain. Tickets are prohibitively expensive. Food is exorbitantly priced. Screenings begin with 20-30 minutes of commercials and trailers, and when the movie starts speakers are blown out, pictures are soft and dim, people are on their phones, and the movie itself is likely to be some IP slop. Why pay more than $20 for a lousy Marvel flick, plus $50 for food, when you could subscribe to Netflix’s ad-free tier for less than $20 a month?

As a vertically-integrated monopoly, Netflix could embrace the consumer-friendly face (while naturally leaning into the creative-crushing backroom practices) of Old Hollywood studios. It could deploy all its Silicon Valley know-how to innovate movie theaters, bringing them into the 21st century and create better experiences that viewers want to pay for. It could bring ticket prices down to a place where audiences can afford to return. Netflix would be paying itself, after all, not splitting the box office with theater owners. And it could justify all of this by treating the movie theater as a kind of loss leader that gets people in the door and encourages them to sign up for Netflix — sort of how Best Buy would offer cheap CDs and DVDs as a way to get customers in the door and sell them a high-priced refrigerator.

Of the major theater chains — AMC, Regal, Cinemark, Alamo Drafthouse — AMC is in the most precarious spot. It was briefly a meme stock during the pandemic, but since then its share price has plummeted, down now to $2.27, which is 99% below its meme-time high. And despite its viral ad featuring Nicole Kidman uncannily “watching” a movie in a theater, AMC blew up that goodwill by earlier this year saying it would run 25-30 minutes of ads before the trailers. (It quickly walked this back, but the PR damage was done.)

AMC, globally, has close to 900 theaters and nearly 10,000 screens. If Netflix wanted to buy up a theater chain — and it absolutely should — AMC would immediately give it the scale and footprint that would allow it to participate, and compete, in the theatrical distribution space.

I’ll be the first to admit that this is all very cynical. Netflix has a lot to answer for, in terms of the perverted economics and aesthetics warping the output of Hollywood circa 2025. But so does Disney. What are MCU movies if not big-budget episodic TV in the Netflix slop mode? And, frankly, so does Warner Bros., who, under the leadership of world-class mediocrity David Zaslav stripped WB and HBO of its prestige and clout and opened the door for it to be acquired in the first place.

So, yes, all of this is heavily caveated. But I love movies too much to wallow in frustration, to gnash my teeth and rend my garments and tithe at the altar of A24 — itself mutating into late-stage Miramax under pressure from its more than $200 million in VC investments. America’s movie ecosystem needs a healthy Hollywood and a functioning system for studio filmmaking. And right now, that looks like Netflix. (Just writing that sentence makes me want to barf.) And Netflix, by acquiring Warners, is starting to look like a studio in the classic mold. It should probably start acting like one.

Comments ()