From the Archives: "The Secret Agent" Filmmaker Kleber Mendonça Filho on Cinema and Memory

"Two historic cinemas in downtown Recife are very successful as places of congregation. Otherwise people go to the shopping malls, which is a completely artificial environment designed to make you spend money. And I'm not into practicing my citizenship as a person in a shopping mall."

The 2026 Academy Awards nominations are out, and filmmaker Kleber Mendonça Filho’s brilliant The Secret Agent is up for four Oscars: Best Picture, Best Actor (Wagner Moura), Best International Feature, and Best Casting (sigh). It deserves them all. Set in Recife, Brazil, in 1977, in the waning days of the military dictatorship — "a period of great mischief," as some text tells us at the start — the film centers on Armando (Moura), an academic, widower, and father, as he awaits his chance to flee the country amid persecution and a hit put out on him by a malignant, reptilian industrialist. The nearly three-hour film is deeply soulful and humane, stuffed with fully realized characters whose simple ambition to stay alive and maintain their humanity amidst the ambient repression and outright horror around them is hard to shake off.

The film is a political thriller, I suppose, insofar as there are politics and it’s thrilling. But like all of Mendonça Filho’s work, it’s impossible to peg The Secret Agent to a single genre. And anyway, that’s the wrong read. This is the cinema of memory: not only of an era in danger of being forgotten, but of a place and of people that are being lost. As Mendonça Filho showed in his previous film, the documentary Pictures of Ghosts, Recife was once a throbbing hive of culture — particularly cinema — but beginning in the 1970s, the era of suburbanization and shopping malls gutted Recife’s core districts, like its downtown. Shops and movie theaters closed, bad press hyped up crime, and benign neglect finished the job. The Secret Agent is an evocation of Recife as it heads toward that cliff. The city is still vibrant, though the danger is escalating: 90 people die during carnival (the corrupt police chief insists the final tally will top 100); a human leg is found inside a dead shark.

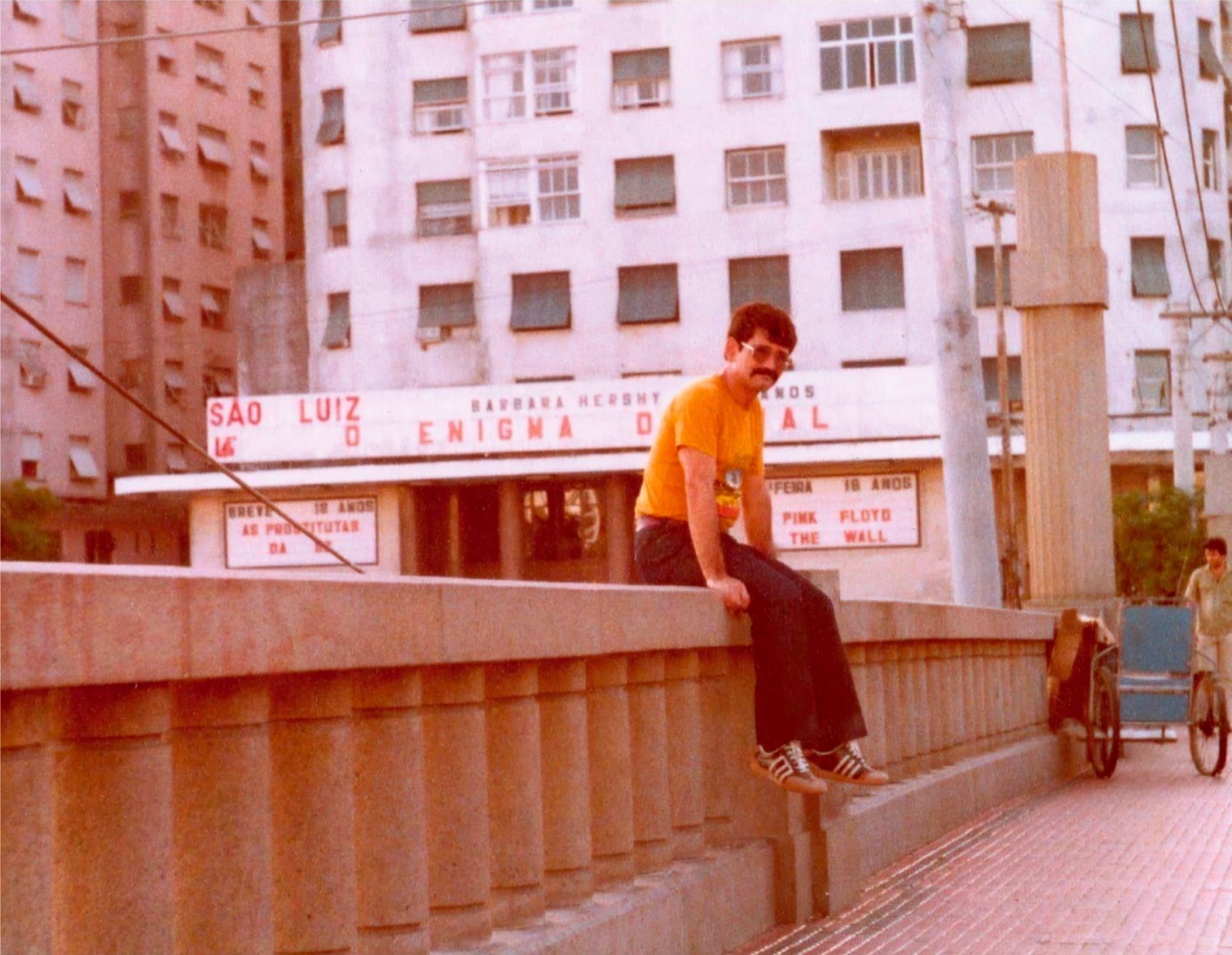

That last plot point, a reference to Jaws, which dominated Recife’s theaters along with the remake of King Kong, in 1977, is a kind of slippage between this movie and Pictures of Ghosts, the membrane separating the films incredibly permeable. The Cinema São Luiz movie palace is a central character in Ghosts; it’s where Armando’s father-in-law Alexandre works as a projectionist in Secret Agent. Alexandre was the name of the projectionist at the Art Palácio theater, the demise of which Mendonça Filho documented as a college student; the fictional Alexandre conjures the real one: he walks the same way, has the same haircut and facial hair, same body type — it’s as if his ghost occupies the new film. There are shots in the documentary, like a projectionist at the São Luiz looking out on Recife, recreated almost exactly in Secret Agent.

Often, it feels like The Secret Agent takes place within Pictures of Ghosts — a moment in Recife’s past captured in a newspaper report placed near a page of movie showtimes. So it felt like a good moment to share an interview I did with Mendonça Filho in October 2023, during the New York Film Festival, about Pictures of Ghosts that has never been published. (No one bit on my pitches at the time, alas.) We talk about the film, movie theaters, and the present and future of moviegoing. The interview has been edited for clarity.

When did you realize that movie theaters — especially these movie palaces — were more than just places to go see a movie, but more kind of important to the civic fabric of your place?

It must have been when I was about 20. I grew up in Recife, which had an unusual selection of great movie palaces. I spent my teenage years living in England with my mother — she studied in England — and when we moved to England I discovered the movie palaces in London, in Leicester Square. And that had a huge impact on me. Not only the actual places but the presentation, projection and sound and 70 millimeter. That was really something. When we went back, I was lucky because I didn't feel that I was — I mean, the cinemas in Recife were not as good as the ones in London, but they were still really, really good and exciting. So this thing just kept happening. But at the same time, I noticed that the cinemas were now closing and some of them were just ruins and closed, abandoned buildings. That for me was always an interesting image and a very complex feeling because I was very much aware that they were historic places. They meant something for a lot of people.

I remember one day, it was in the early ‘90s, I was in university and I was in a bus. And this lady, she comes to the bus driver and says, “Does the bus stop at the Rivoli Cinema?” And he didn't even skip a beat. He says, “Yes, it does.” It stops at the Rivoli Cinema.” But I knew that the Rivoli Cinema had been gone for 13 years by that time. So it was still a place of reference for that woman and for that bus driver. And they didn't even mention that it didn't exist anymore because it was still very much alive in their personal maps for that region.

So those things, I had that in mind when I shot a lot of VHS at the time and took photographs of those cinemas. And it happened that I witnessed a number of them closing before my eyes. It's something that I'm fascinated with. Aquarius has a scene where you can see one of those cinemas, which I featured in Pictures of Ghosts. Neighboring Sounds has another sequence where they visit the ruins of a cinema. So it's something that I'm completely fascinated by and I'm happy that I got to make this film.

Yeah. I remember when I was in college seeing a photo in a book from the '60s, I think, of a silent movie star in the ruins of a movie palace and she's sort of gesturing very theatrically…

Oh, yeah. I think it's... From Sunset Boulevard... Gloria Swanson, yeah.

That's right. That picture has stayed with me. I've lived in New York for 15 years and you walk around enough and you can see the architectural signposts that there was a theater at this place. I went to a new multiplex on the Lower East Side, and across the street is a kind of dollar store and all this stuff crammed into a building. But around the corner, you can see the fire escapes, and, I thought, "That was a movie theater."

It's archeology. It's urban archaeology. In the late '90s, I was in a supermarket in São Paulo. I was at the cashier about to pay, and then I look up and I see — it's a supermarket, right? — I see the portholes for the projection. So this place used to be a cinema. Crazy feeling.

My wife and I took our daughter to see this Baroque chamber or music performance in an old house that is now a kind of Christian retreat. The performance was in the library — a really beautiful space — and I look up and there are those projection portals there, too, because in the 1920s, the woman who owned the house used to show silent movies. It's fascinating to encounter these sorts of things, because it really shows how prevalent theaters were and how prevalent moviegoing culture was and how far we've come from that.

You get into this a bit in the film, but I'm curious, what is the sort of civic importance of a movie palace, and of moviegoing? And is there one?

Well, yeah, I think cities — I mean talking specifically about the municipality and let's say that the mayor's office, you know, the politicians who run a city, they should often ask themselves... So there is a movie theater. It's in trouble now. Is it in the best interest of the city for us to do something and keep that place going? A place which brings together thousands of people every week, on the street. Or is it more interesting for the city to have a car park or a drug store or a supermarket or a bank? I don't think many cities have asked that question, have asked themselves that question.

Right now in São Paulo, there's a cinema which is right on the street, it's on the sidewalk, it's not in a multiplex or a shopping mall. And it's in dire straits because it has lost its sponsor. And the question that the city of São Paulo has to ask itself is: Is it more interesting for the city for us to lose this cinema, or can we do something about it? Can we cut the taxes and make sure that it exists? Because I really think it's an intelligent decision. And this is what has happened to two cinemas in Recife, and they are very successful as places of congregation, young people discovering films in a historic place in downtown Recife. Because otherwise people go to the shopping malls, which is a completely artificial environment designed to make you spend money. And I'm not into practicing my citizenship as a person in a shopping mall. I can go to shopping malls to buy something, to buy underwear, or to do errands, run errands, but not to take my kids and go for a walk in a shopping mall. It sounds like a sick idea.

There's an interview with you in the press notes, and you say about architecture, "My own observations on spaces and cities are not technical, but they are based on my understanding that these are reflections of human nature interacting with society and with capitalism, or being (re)shaped by both." It's a really interesting idea. But I'm curious — specifically to what we're talking about, the movie palaces and what's happening with cities — what does the architecture of those places and their kind of demise say about that interaction?

I think the industry finds new ways of making money, basically. So, for example, in the '50s, when television came along, the industry had to cut down on the number of movie theaters because now television also had this very charming use of pictures. But pictures were not restricted to only to movie theaters. Now you could actually see pictures at home on television. And it strikes me that every time the industry brings something new, a new product, it has to get rid of what came before. And I don't really... I'm all for adding new experiences and not having to subtract anything.

For example, when compact discs, CDs, came along, we were told that vinyls were crap and we had to get rid of vinyl discs. And I still remember in the late '80s, I remember seeing like 50, 70, vinyl records just thrown out into the trash because people had been told that they were bad and CDs were the future. Thankfully, in my family, we kept all the vinyls, and we started buying CDs also, which I think is an interesting idea. I use streaming. I see films on Netflix, on Amazon, but I'm still going to the cinema. And I also love to buy Blu-rays. I like adding new experience.

And think what happened to the cities is, when shopping malls came and multiplexes came, in Recife it's a very — this could be another film, because there was a blitzkrieg of bad press in the late '70s and early '80s. And not a coincidence that this is exactly the moment they were investing in the first shopping mall — a blitzkrieg of bad press about downtown Recife. So after a few years of opening the newspaper and watching television and listening to bad news on the radio about the downtown area — it's dirty, it's dangerous, it's full of drug addicts — we have the solution for you: shopping mall. So this worked really well over a period of 10 years, and in 10 years, the downtown area just went down. And then with that, the last remaining movie palaces closed. So there is a whole logic to how things happen.

In my mind, they could have opened a new shopping mall and then a second, third, the fourth, and the fifth shopping mall, but still the downtown area would be a different option, something different for you to do, for you to choose. But the whole idea is that you don't choose anymore. You have to do what we want you to do. It's almost like, you know, the way you have a roof and then the engineer organizes the way the water flows and it goes down in the drain pipe. It's exactly the same idea, but in a city. And the drain pipe will lead you to the shopping mall. So this is a really interesting system that was planned and put together to make that system work. And for me that's a whole new, I don't know, documentary that somebody could do. I'm not sure I would be interested in making that film, but it is a very interesting story. If you go to the archives and look at all the news pieces, all the television pieces about how terrible the downtown area has become, you will understand how the whole thing works.

Yeah, it's interesting to think about it almost like it's engineered for anti-choice. It's sort of zero sum, like this or that...

Like CDs and vinyl.

Right. I recently had a conversation with a friend and he was making fun of DVD players. And I had to say, I still have DVDs and Blu-rays. I still watch them that way. You can have both.

And by the way, the same thing now is being done to streaming because people actually believe that they can find anything, anywhere, at any time on streaming. And this is not true.

Do you see your film as having a place in this broader argument, or broader debate, that's happening now, especially after the pandemic, about the role of the movie theater? I feel like people talk about the movie theater as either a relic, it's archaic and it should go away, or it's exclusive and you can charge $30, $40 a ticket and make it an experience. To me, both choices miss the reality of what a movie is and the space of movies and culture. What do you think your film can add to that debate, if anything?

Sometimes I ask myself if it's because I'm privileged to be a filmmaker and to get to travel to film cities. My own city is a film city. Rio is a film city. Paris, New York. But there are many other towns and cities which offer you the experience of going to an amazing place and discovering a film. So I like to think that we are still doing well, but I think we also have to struggle against some kind of modern idea of what filmgoing is.

For example, it's really tough to be watching a film and people are using their phones. You know, this is a terrible problem. Some theaters have an incredibly aggressive strategies against that. I find it's Monty Python-level funny in some of the things that I've heard. I think that Alamo Drafthouse does some pretty harsh... <laughs> I love it, by the way. But it's not always like this, and I admit that sometimes, a film is screening in Recife and I can see it on Netflix, I might, depending on the day, choose to stay at home and see it in my very good sound system and great television or projection. But I really think we got to have the choice. We should be able to choose.

After the pandemic, audiences largely stayed away in Brazil. We are still struggling and people are coming back now. Pictures of Ghosts is actually doing really, really well in cinemas. In the beginning, people said, "Well, it's doing well for a documentary." And now, it's actually doing well and "for a documentary" is not even being used anymore. So I tend to be optimistic. And I'm optimistic because every day, especially with the release for this film — which we focused on many non-multiplex screens for this film in Brazil — every day I would read a very young viewer saying that he or she discovered not only the film but the place where she went to see the film. And so that makes me optimistic. I'm usually a more optimistic person than a pessimistic person.

In the film, you talk about the São Luiz and you say, "I don't know of anywhere in Recife that's as unanimous as this." I've never heard anybody describe a theater or any space like that, as "unanimous." Could you explain what what you meant by that?

Yeah, it's a place that no one has ever said anything negative about, the São Luiz. The São Luiz is a place that everyone, and I say this... The very first film I saw was at the São Luiz in 1973, a Tom and Jerry marathon, and it's just a place that everyone loves. And that explains why it survived. Because all the other movie palaces closed, but then when it came to the São Luiz, everyone, the city, said, "No, no, no, no, not going to happen. We will save this one." It was not only cinephiles, but it was government, it was municipality, it was business people, it was, you know, the popcorn guy. Everybody basically worked to make that happen. And even the company, which built the São Luiz, they made sure that they did not sell it to a church. They did not sell it to anything... They approached the government and said, "Please buy it. We would love to keep it, but we just cannot make it work. We will really give you a kind of lower than what would the market would not normally ask, but we just want to make sure that the São Luiz is saved because it was our grandfather who built it, it's named after him, and it's a very special place." And it might sound like a fairy tale, but that's exactly how it happened. It has some kind of charm and seduction that just basically woos everyone, and that's why it still exists. It's a crazy beautiful, crazy strange and amazing place.

Comments ()